Wing Chun Kuen

(詠春拳)

Introduction

“Wing Chun Kuen” (詠春拳) or (Yongchun Quan) translates as “Singing Spring Boxing.” “Wing Chun” (詠春) means “Singing Spring,” and “Kuen” (拳) means “fist” or “boxing. Wing Chun is a Kung Fu system that was developed in southern China approximately 400 years ago.

This style is characterized by its pragmatic approach to combat, in particular thanks to the use of short and direct techniques that aim to immediately obtain the advantage during a fight. The redirection and utilization of the opponent’s force, combined with a simultaneous and fluid counteroffensive, make Wing Chun a particularly effective style and accessible to everyone, regardless of age and body strength.

The system aspires to be both internal and external, integrating numerous elements of Taoist philosophy in its concepts and principles (Flow, yield, wu-wei, yin-yang etc.).

The Legend

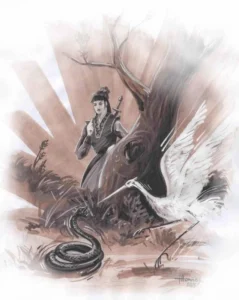

According to legend, following the destruction of the Southern Shaolin Temple during the early Qing Dynasty (17th-18th century), five fugitive monks, all martial arts experts, managed to escape. One of them, a Buddhist nun named Ng Mui, sought refuge in the mountains near a small village. There, she is said to have observed a battle between a snake and a crane. The snake, using its fluid and unpredictable movements, attempted to strike the crane, while the crane skillfully deflected attacks with its wings and countered using its beak. Inspired by this, Ng Mui developed a new martial system based on efficiency, directness, and adaptability, which later became known as Wing Chun.

According to legend, following the destruction of the Southern Shaolin Temple during the early Qing Dynasty (17th-18th century), five fugitive monks, all martial arts experts, managed to escape. One of them, a Buddhist nun named Ng Mui, sought refuge in the mountains near a small village. There, she is said to have observed a battle between a snake and a crane. The snake, using its fluid and unpredictable movements, attempted to strike the crane, while the crane skillfully deflected attacks with its wings and countered using its beak. Inspired by this, Ng Mui developed a new martial system based on efficiency, directness, and adaptability, which later became known as Wing Chun.

During her time in the village, Ng Mui encountered a young woman named Yim Wing Chun, who was being harassed by a local warlord or military officer who sought to force her into marriage. Sympathizing with her plight, Ng Mui offered to teach her the martial system she had developed. Yim Wing Chun diligently trained under Ng Mui’s guidance and was eventually able to defeat the oppressive officer, securing her freedom. Later, she married Leung Bok Chau, a merchant who became the first to pass on the system, naming it “Wing Chun” in honor of his wife.

A brief history of Wing Chun

The origins of Wing Chun have been passed down through stories and legends. While these tales add to its mystique, they often lack solid historical proof. This section looks at Wing Chun’s development using academic research and historical records, focusing on real social and cultural contexts rather than folklore. By relying on historical sources, we narrow our view but gain a clearer picture of how Wing Chun evolved in the 19th and 20th centuries. Examining social changes, political struggles, and secret societies helps us understand how the system took shape and became what it is today.

(For detailed information, we recommend checking out our articles in the blog section.)

The Qing dynasty decline and the Rise of Resistance

An illustration depicts a Chinese opium den in the 19th century Source: Britannica

The Qing dynasty was established by the Manchus, an ethnic minority from the northeast who overthrew the Ming dynasty in 1644. Although they ruled China for nearly three centuries, they were often seen as foreign rulers by the Han Chinese majority. Policies favoring Manchu elites and suppressing Han resistance fueled resentment, leading to many uprisings and the formation of secret societies aiming to restore Han rule.

At the same time, China faced growing pressure from Western powers. The Qing dynasty, weakened by internal corruption and economic difficulties, suffered humiliating defeats in the Opium Wars (1839-42, 1856-60). These wars forced China into unfair treaties, giving away land and trade rights, which further destabilized the country. These losses not only drained China’s economy but also exposed the empire’s inability to defend itself against foreign aggression. As a result, widespread unrest and dissatisfaction grew, leading to rebellions and the rise of resistance movements.

Southern China’s Isolation and Secret Societies

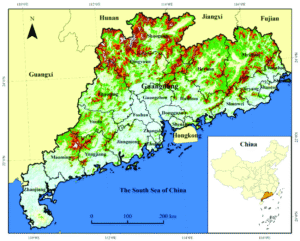

Guangdong province, China Source: ResearchGate

Southern China, especially Guangdong, is geographically separated from the rest of the empire by the Nanling Mountains (南岭). This isolation allowed these provinces to develop distinct cultural identities, including their own martial arts traditions. However, as foreign influence grew, the region faced increasing instability. Japanese pirate incursions added to the overall insecurity, disrupting trade and local economies. Traditional ways of life began to collapse, leaving many communities struggling to survive.

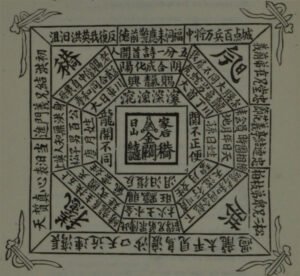

Certificate given to Tiandihui’s new member Source: Source: BiblioAsia

The Hakka people, a migratory ethnic group originally from the central plains of China, were among those who suffered the most. They often faced land displacement and discrimination from the dominant Cantonese Han population. As tensions grew, many sought refuge in secret societies that opposed the Qing government and aimed to protect their members. One of the most influential of these groups was the Tiandihui 天地会 (Heaven and Earth Society). While often associated with anti-Qing resistance, many branches of the Tiandihui were primarily engaged in criminal activities such as gambling, opium trade, and extortion.

Initiation into the Tiandihui involved elaborate rituals, where new members swore oaths before an altar with incense and blood. They performed the “kowtow,” a ritual bow, as a sign of devotion and loyalty to the brotherhood. These ceremonies reinforced strong bonds of secrecy and unity among members, making the Tiandihui a powerful underground network.

The Tiandihui also provided shelter to rebels, dissidents, and skilled martial artists, who sought protection within its ranks. These groups played a significant role in preserving and refining martial arts traditions that would later influence Wing Chun’s development.

The Red Boat Opera and the Transformation of Wing Chun

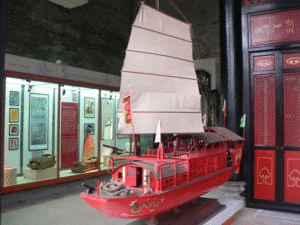

Cantonese Red Boat Source: Foshan News

While legends trace Wing Chun’s origins to the Southern Shaolin Temple, no historical evidence confirms its existence. What is certain is that the style predates the 19th century but underwent a significant transformation during the mid-1800s, shaped by Hakka and Cantonese martial artists who found themselves on the same side during the Red Turban Revolt (1854–1856). This anti-Qing uprising, which spread across southern China, brought together fighters from both communities—historically divided by cultural and political tensions.

A major incubator for this transformation was the Cantonese Opera, particularly its Red Boat troupes. These traveling performers were more than entertainers; many were skilled martial artists whose acrobatic training made them agile fighters. The Red Boats, which carried them from town to town, became meeting points where techniques were exchanged and refined. For the first time, Cantonese and Hakka practitioners worked together, shaping Wing Chun into a compact, efficient system designed for close-quarters combat—well-suited to countering the wide, open techniques of Choy Lee Fut 蔡李佛, the style of the empire.

As these martial artists gained influence, Qing authorities took action to suppress them, culminating in the burning of Foshan’s main Cantonese Opera House, a major blow to the movement. Many Red Boat performers went into hiding, passing their knowledge in secret. Figures like Wong Wah Bo and Leung Yee Tai are often credited with refining Wing Chun during this period, though historical records remain scarce.

From Leung Jan to Ip Man: The Path to Modern Wing Chun

Dr Leung Jan Source: Culture Hong Kong

After the rebellion, Wing Chun kept evolving, reaching a turning point with Dr. Leung Jan, a respected doctor and skilled fighter from Foshan. Known as the “King of Wing Chun”, he was the first master with documented historical records. Leung Jan learned from multiple teachers and brought together different elements of the system, including the pole and swords. Though famous for winning challenge matches, he never sought to teach publicly—martial arts weren’t seen as a respectable profession, and his focus remained on medicine. Still, he passed his knowledge to his two sons, Leung Bik and Leung Chun, and to Chan Wah Sun, a tough money changer who would later play a key role in Wing Chun’s future.

Chan Wah Sun was more than just a student—he carried forward both Leung Jan’s fighting skills and his medical expertise. Some say he discovered his teacher by chance, running a stall near Leung Jan’s pharmacy. Either way, he trained in secret until Leung Jan retired around 1895, finally allowing Chan to teach openly. In 1905, Chan Wah Sun became the first person to open a public Wing Chun school, marking a shift from private teachings to a more structured and accessible system. He went on to train a handful of students, but one name stood out: Ip Man. Decades later, Ip Man would bring Wing Chun to the world, ensuring the art’s survival beyond its roots in Foshan’s secret circles.

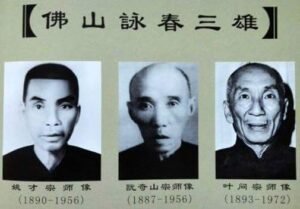

Foshan and the Three Heroes of Wing Chun

The 3 Heroes of Wing Chun Source: Facebook

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Wing Chun was no longer a hidden art. After the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, China was thrown into chaos, with warlords and revolutions reshaping the country. During this period, Wing Chun masters who had once trained in secret began teaching openly. One key figure was Ng Chung So, a senior student of Chan Wah Sun. After Chan retired, Ng became the main instructor in Foshan, helping shape the next generation of fighters. He mentored Ip Man, Yuen Kay San, and Yiu Choi, later known as the Three Heroes of Wing Chun, for their role in carrying the art forward.

Wing Chun’s worldwide expansion is largely thanks to Ip Man. When the Communists took power, he fled to Hong Kong, where he refined and taught the art. The city’s thriving martial arts scene, fueled by masters escaping mainland China, created a highly competitive environment. Ip Man’s structured approach made Wing Chun more accessible, attracting students from all backgrounds. But it was his most famous disciple, Bruce Lee, who truly put Wing Chun on the global stage. Through his Hollywood success, Lee introduced the world to the art, making it a household name. Today, most Wing Chun schools trace their roots back to Ip Man, cementing his legacy as the father of modern Wing Chun.

It is important to emphasize that Wing Chun has developed through multiple lineages, each with its own evolution. While we have highlighted key figures such as Ip Man, Yuen Kay San, and Yiu Choi, many other branches have also contributed to shaping the art. In upcoming articles, we will explore these lineages, with a special focus on Weng Chun (永春, Eternal Spring)—a system that may be an ancestor of Wing Chun or, at the very least, closely related in its development.